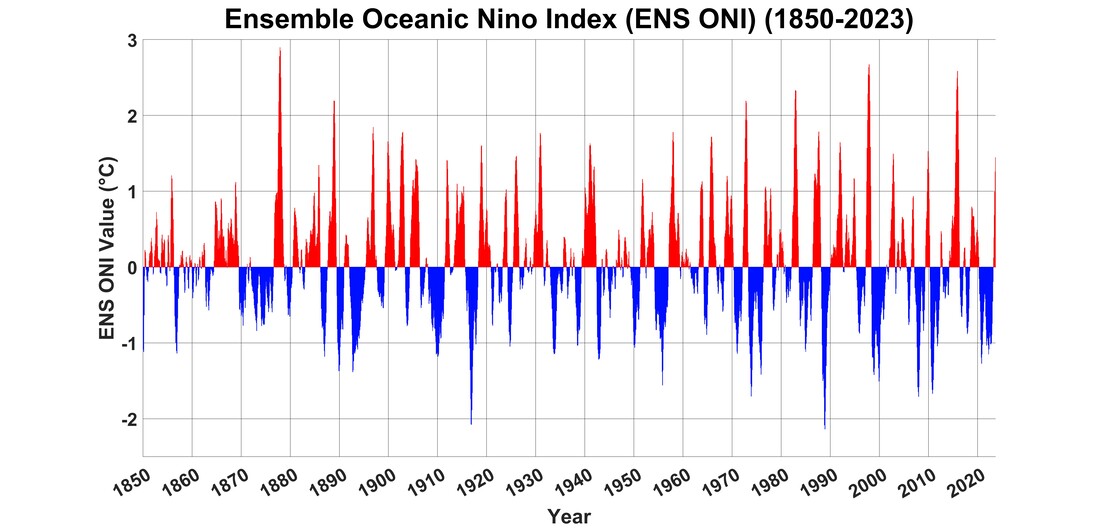

Ensemble Oceanic NINO Index (ENS ONI)

Created using Matlab 2022b

Note: The land-sea mask in Kaplan Extended SSTv2 causes discontinuities (white space) near the edges of the figure.

Created in Python v3.9

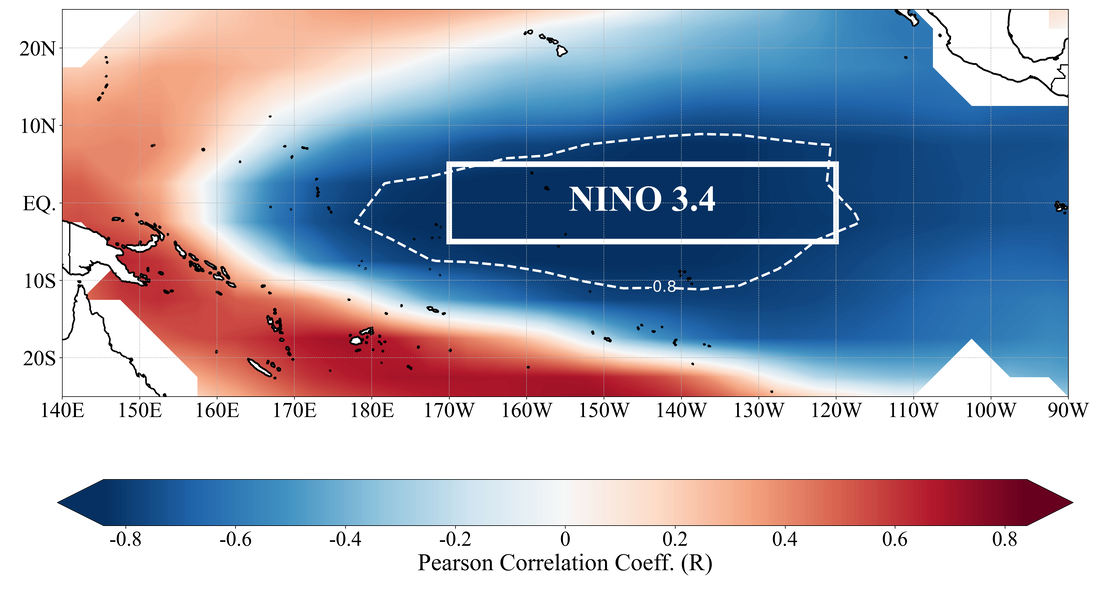

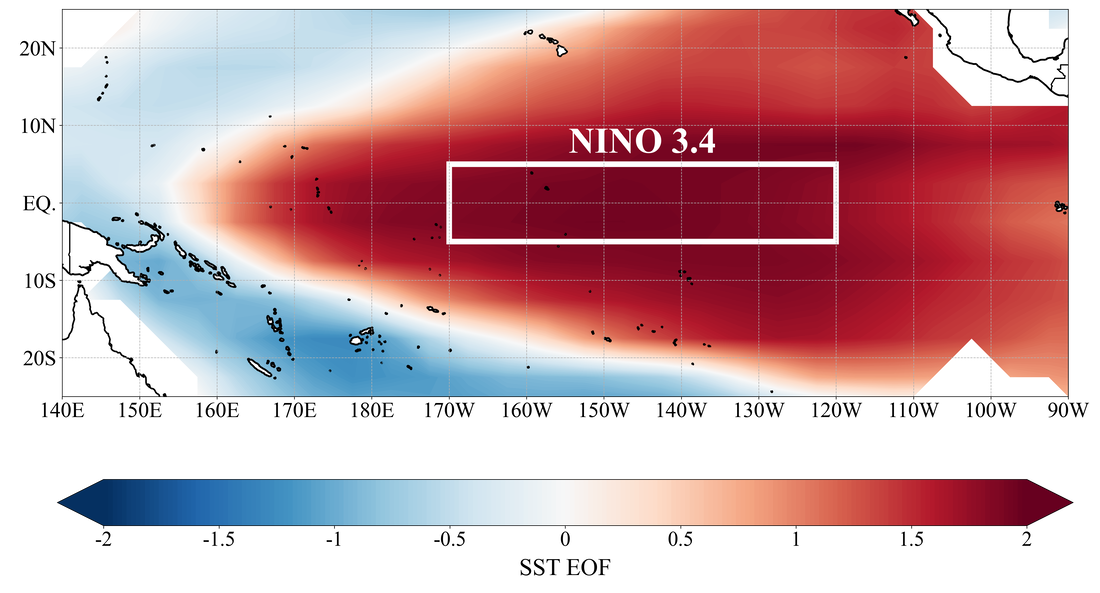

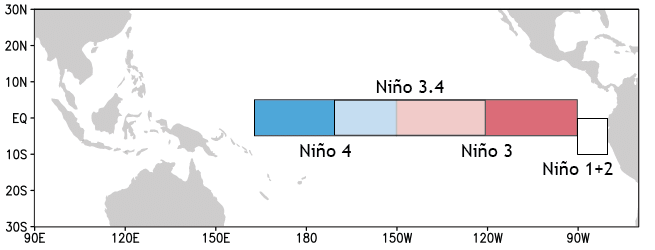

The NINO 3.4 region (5°N - 5°S, 170°W - 120°W) is demarcated by a solid white box.

Note: The land-sea mask in Kaplan Extended SSTv2 causes discontinuities (white space) near the edges of the figure.

Created in Python v3.9

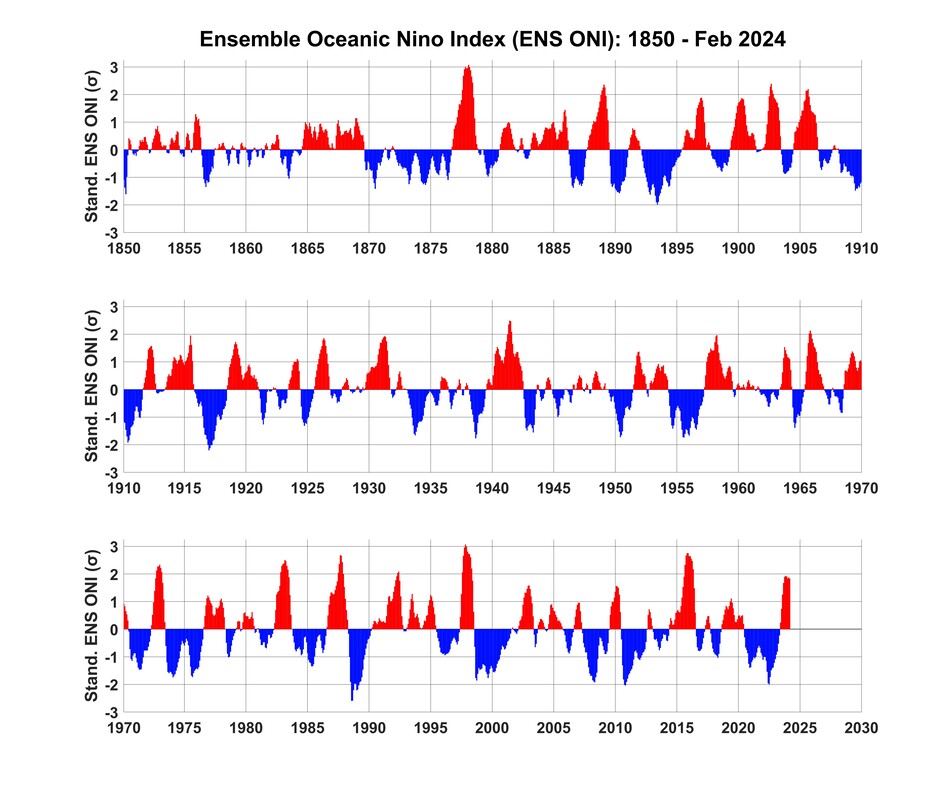

MAJOR UPDATES TO THE ENSEMBLE OCEANIC NINO INDEX (ENS ONI)

July 2022: MERRA-2 reanalysis was extended from 2016 to the present

April 2022: Raw monthly ENS ONI input from all 32 SST + reanalysis datasets have been released

February 2022: ENS ONI published in the International Journal of Climatology

(Accepted PDF): The Ensemble Oceanic Nino Index (Webb & Magi, 2022)

May 2021: ENS ONI median definitions are now presented in percent instead of raw numeric values to allow for more intuitive interpretations of the data.

April 2021: ENS ONI median definitions (described below) were added to the suite of available output.

March 2021: ENS ONI data for 1850-1864 has now been released, several datasets were added, and the juxtaposition of ENS ONI's 30-year sliding base periods were updated to be more symmetric with the 5-year periods (Dr Brian Magi, person comm). The pre-1865 extension of the ENS ONI reveals a potential El Nino event in 1855-56, which is strongly supported by recent work from Lin et al (2020) depicting this particular El Nino to be associated with the 2nd worst drought during the Qing dynasty in China. Applying a 30-year sliding median to Madras SLP (1796-2003) reconstructed by Allan et al (2002) also reveals substantial evidence of an El Nino in 1855-56 w/ 30-year median SLP anomalies exceeding +1.2σ in November 1855, which is near the top 10% of all Novembers in 1796-2003.

Experiments with pre-1850 instrumentally-based data like the aforementioned Madras SLP and available reanalysis over this period (like NOAA 20CRv3 (Slivinski et al (2019)) and corroboration with documentary sources such as

Garcia-Herrera et al (2008), Ortileb (2000), & Quinn et al (1987) reveal fairly substantial evidence of an El Nino in the winter of 1845-46.

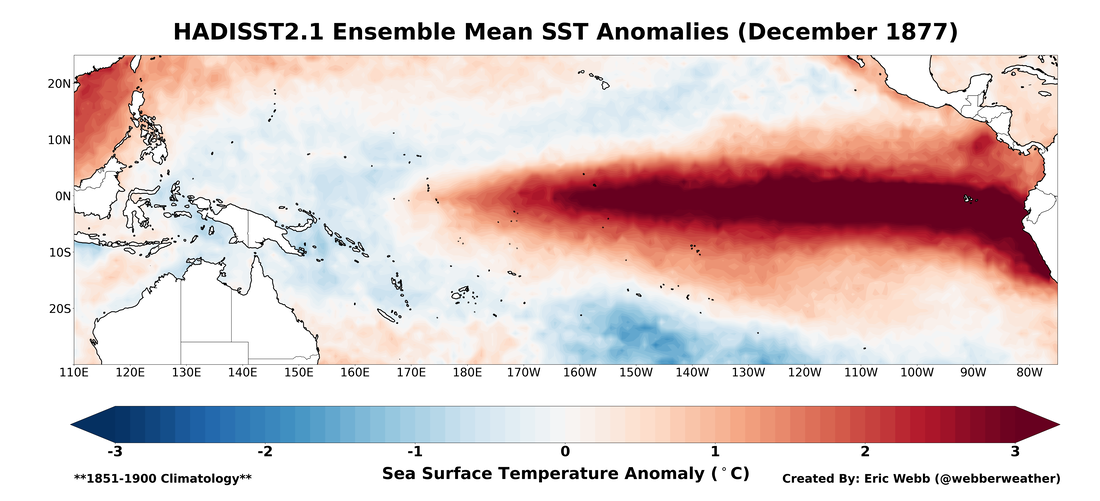

Simple Ocean Data Assimilation version 2.2.4 (SODAv2.2.4) (1871-2010) (Giese and Ray (2011)), ECMWF's Ocean Reanalysis System 5 (ORAS5) (Zuo et al (2019)) (which is used for the operational ECMWF model), & NASA's Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications Version 2 (NASA MERRA2) (Gelaro et al (2017)), have been added to the ENS ONI, further improving the overall quality of the index and accompanying estimates of inter-dataset spread, especially for the 1871-1900 period when few datasets are available and most SST reconstructions (e.g. HADISST1) that rely on modern ENSO behavior to reconstruct ENSO when data coverage is sparse, may underestimate the amplitude of major ENSO events like 1877-78 (Giese and Ray (2011)).

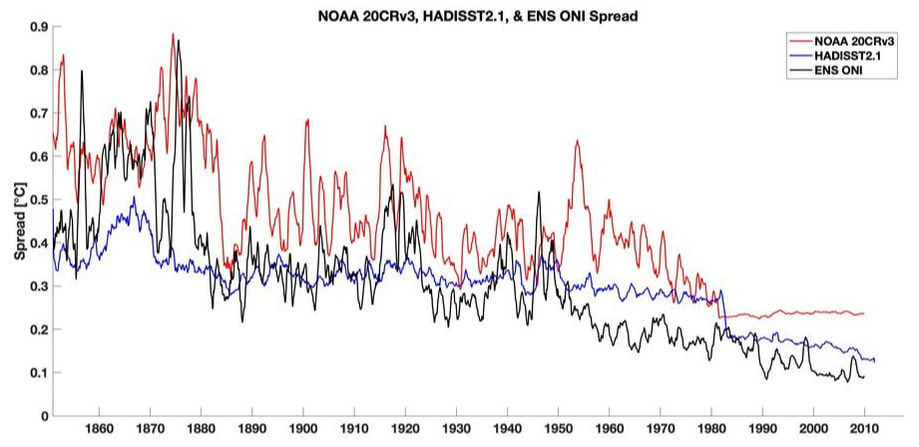

For comparison purposes and to further validate the legitimacy of ENS ONI's first-order estimates of structural uncertainty that emerge between datasets, ENS ONI's inter-dataset spread is now also directly accompanied by other published estimates of NINO 3.4 region spread from NOAA's 20CRv3 (Slivinski et al (2019)) and HADISST2 (Titchner and Rayner (2014)) (See figure and the excel sheet below).

The previous quality control procedure used to filter out potentially spurious data was discontinued as the median used to derive the index here is fairly robust to outliers.

An additional excel sheet with peak ENSO event intensities (in °C) has been added to the list of deliverables provided below on this web page.

October 2020: HADISST2.1 was added to the ENS ONI, significantly increasing the quality of the ENS ONI prior to 1900, and the new quality control procedure used to filter out potentially spurious data in the ENS ONI is significantly less stringent. OISSTv2 was upgraded to OISSTv2.1, which may slightly impact recent ENS ONI data.

ENS ONI now uses median SSTs instead of mean SSTs from available datasets at each time step to better protect the ENS ONI against outliers and preserve the amplitude of pre-1950 ENSO events. Utilizing the median SST also more accurately depicts well known asymmetries in ENSO amplitude stemming from more efficient Bjerknes feedbacks and stronger non-linearities between SSTs, surface winds, and locally forced convection in El Ninos. To better reflect this asymmetry, ENSO event intensity definitions were altered from, with "Super La Nina" no longer being utilized. However, keeping in spirit of the original ONI, ENS ONI still utilizes 3-month running means of monthly ONI values to determine tri-monthly ENS ONI values. The ENS ONI is also now accompanied by uncertainty estimates, determined by inter-dataset spread at each monthly time step, approximated as 2σ, generally corresponding to 95% level statistical significance.

July 2019: ERA-5 was added to the analysis & interpolated to a 1x1 degree grid to make it more comparable to other datasets used in the ENS ONI. Its addition resulted in little notable change in the ENS ONI after 1964. The ENS ONI quality control procedure was reevaluated for the 1877-78 El Nino, resulting in more realistic amplitude evolution during the growth phase of this "Super" El Nino in 1877. Changes in the 1877-78 El Nino also implicated nearby portions of the record, leading to an extremely modest modification of other ONI values from 1865 to 1890.

June 2019: HADSST4 was added to the analysis, resulting in a slight increase in amplitude of most pre-1950 ENSO events due to better constraint of quality control procedures. The standard deviation of available SST datasets used in the ENS ONI is now also provided.

Introduction

Aside from the large number number of datasets and uncertainty estimates, one of the primary methodological differences between the ENS ONI and the CPC ONI is the choice to use climatological base periods based on median SSTs instead of mean SST. This allows the ENS ONUI to better characterize ENSO asymmetry, as SST climatologies may be slightly skewed towards El Ninos (e.g. An & Jin (2004)) and makes the ENS ONI more robust to outliers, which is important early in the record when SST uncertainty is large and there are few(er) datasets available to constrain the ENS ONI. A more detailed description of methods is described in Webb and Magi (2021)

The ENS ONI is intended to be a predecessor product to the Extended MEI version 2 (MEI.extv2), which is currently in production. For more on MEI.extv2 see my 100th Annual American Meteorological Society (AMS) Conference poster presentation: "Reanalysis of the Extended Multivariate ENSO Index"

2020 Master's Thesis on the "Reanalysis of the Extended Multivariate ENSO Index"

NINO 1+2: (0°-10°S, 80-90°W), NINO 3: (5°N-5°S, 90°W-150°W), NINO 3.4 (5°N-5°S, 120°W-170°W), NINO 4 (5°N-5°S, 160°E-150°W)

Data

Although this index exhibits very robust correlations with the Bivariate ENSO Timeseries (BEST), Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI), Extended Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI.ext), this product should be used with caution, especially for prior to 1877 and in/around the first and second World War. The following 32 sea surface temperature, satellite, and reanalysis datasets were utilized in the creation of the ENS ONI at a grid spacing that varied between 1°x1° and 5°x5° latitude and longitude to ensure all were resolving the same types of phenomena in their respective fields. If these datasets weren't explicitly provided with this grid spacing, they were averaged over a number of grid boxes until this criteria was met.

HADISST2.1 (1850-2010)

COBE SST 2 (1850-2019)

HADSST4 (1850-2021)

NOAAs 20th Century Reanalysis Version 3 (1850-2015)

NOAAs 20th Century Reanalysis Version 2c (1854-2014)

ERSST Version 5 (1854-Present)

ERSST Version 4 (1854-2020)

Kaplan's Extended SST Version 2 (1856-2023)

HADISST (1870-Present)

NOAAs 20th Century Reanalysis Version 2 (1871-2012)

SODAv2.2.4 (1871-2010)

IOCADSv3 (1878-2020)

ERSST Version 3b (1880-2020)

COBE SST (1891-Present)

ERA-20CM (1900-2010)

ERA-20C (1900-2010)

CERA-20C (1901-2010)

NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis Version 1 (1948-Present)

HADSST2 (1950-2014)

HADSST3 (1950-2020)

ERA-5 (1950-Present)

WHOI OA Flux Version 3 (1958-2019)

ECMWF ORAS5 (1958-2019)

Climate Analysis Center (CAC) (now known as the CPC) SST (1970-March 2003)

NCEP CFSR (1979-2015)

NCEP DOE R2 (1979-Present)

ERA-Interim (1979-2019)

NASA MERRA (1979-2016)

NASA MERRA2 (1980-2023)

European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative (Sep 1981 - 1988) (ESA SST CCI)

Operational Sea Surface Temperature & Sea Ice Analysis (OSTIA) (Oct 1981-Present)

OISSTv1 (1 degree) (Nov 1981-March 2003)

OISSTv2.1 (1 degree) (Nov 1981-Present)

Aqua/MODIS SST (1 degree) (July 2002-Present)

Coral Reef Watch (CRW) SST (Apr 1985-Present)

ODYSSEA SST (Jan 2021 - Present)

30-Year Climatological Base Period |

ENS ONI Values |

1850-1879 |

1850-1867 |

1855-1884 |

1868-1872 |

1860-1889 |

1873-1877 |

1865-1894 |

1878-1882 |

1870-1899 |

1883-1887 |

1875-1904 |

1888-1892 |

1880-1909 |

1893-1897 |

1885-1914 |

1898-1902 |

1890-1919 |

1903-1907 |

1895-1924 |

1908-1912 |

1900-1929 |

1913-1917 |

1905-1934 |

1918-1922 |

1910-1939 |

1923-1927 |

1915-1944 |

1928-1932 |

1920-1949 |

1933-1937 |

1925-1954 |

1938-1942 |

1930-1959 |

1943-1947 |

1935-1964 |

1948-1952 |

1940-1969 |

1953-1957 |

1945-1974 |

1958-1962 |

1950-1979 |

1963-1967 |

1955-1984 |

1968-1972 |

1960-1989 |

1973-1977 |

1965-1994 |

1978-1982 |

1970-1999 |

1983-1987 |

1975-2004 |

1988-1992 |

1980-2009 |

1993-1997 |

1985-2014 |

1998-2002 |

1990-2019 |

2003-2021 |

Climate Prediction Center (CPC): Monthly Atmospheric and SST Indices

Copernicus Marine Service

ECMWF Climate Reanalysis

ECMWF Copernicus Climate Change Service

Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) Working Group on Surface Pressure (WG-SP)

International Research Institute for Climate and Society

Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut (KNMI) Climate Explorer

Met Office Hadley Centre observation datasets

NASA Earth Observations

NCAR's Research Data Archive

NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory

NOAA's Science Data Integration Group Live Access Server

Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System (PacIOOS) ERDDAP

Discussion and analysis

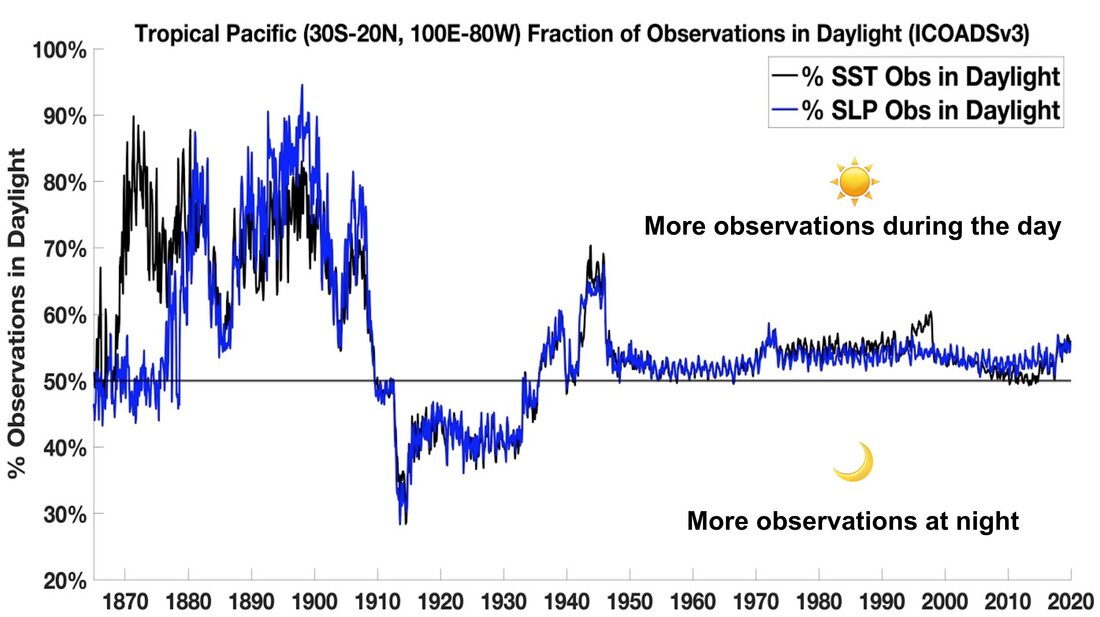

Uncertainty in SST observations

Created using Matlab 2019a

Created using Matlab 2019a

COMPARING ENS ONI TO Independent proxy & documentary records

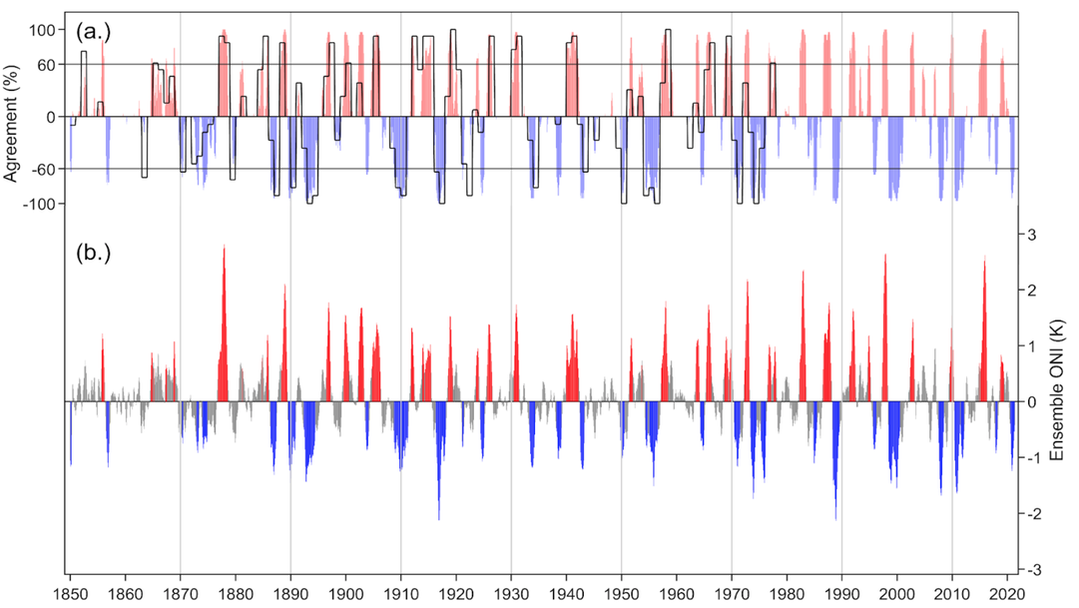

Here, 13 literature sources (Quinn et al (1987), Stahle et al (1998), Cook et al (2008), Braganza et al (2009), Gergis & Fowler et al (2009), McGregor et al (2010), Wilson et al (2010), Li et al (2011), Hakim et al (2016), Anderson et al (2019), Freund et al (2019), Tardif et al (2019), Dätwyler et al (2020), Sanchez et al (2020)) are utilized during their shared, overlapping period (1850-1977), Most of these proxy records have vastly different units and variables, and the written records are qualitative in their classification of ENSO. To facilitate a comparison amongst them, an approach modified from Wolter and Timlin (2011), whereby the annual percentile ranks are analyzed from all proxy + documentary records, and compared to the fraction of institution and literature based definitions (below) based on the Ensemble ONI. The upper, middle, and lower terciles represent El Niño, Neutral ENSO, and La Niña, respectively, except for Stahle et al (1998), which is an SOI-based proxy index where the signs are inverted. The annual fraction of proxy + documentary records that designate El Nino or La Nina conditions is shown by the black line, whereas the ENS ONI % of institution + literature definitions met shaded (red = El Nino, blue = La Nina). For reference, the ENS ONI time series is also plotted (bottom).

Overall, the agreement between instrumental and proxy + documentary records of ENSO is pretty strong even prior to 1950. Unsurprisingly, the largest discrepancies between these 2 independent sources of data exist during the 1850s. For example, proxy + documentary records suggest an El Nino in 1852-53 and a La Nina in 1863 are significantly muted/underestimated by instrumental data, whereas a moderately-intense La Nina depicted during the winter of 1856-57 in the ENS ONI may be an artifact.

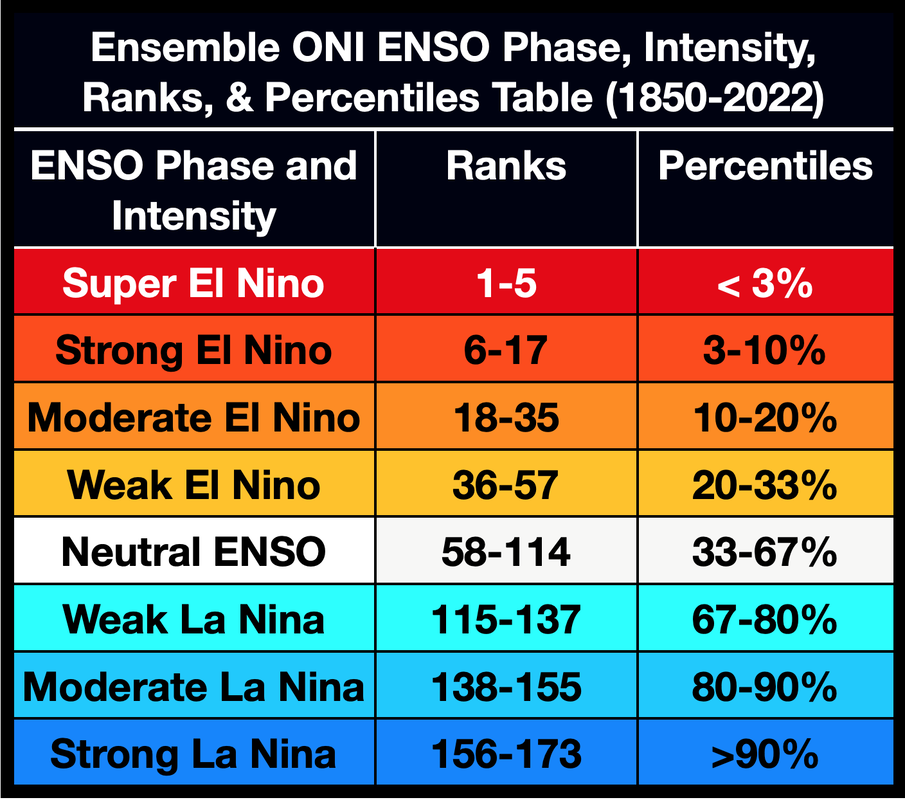

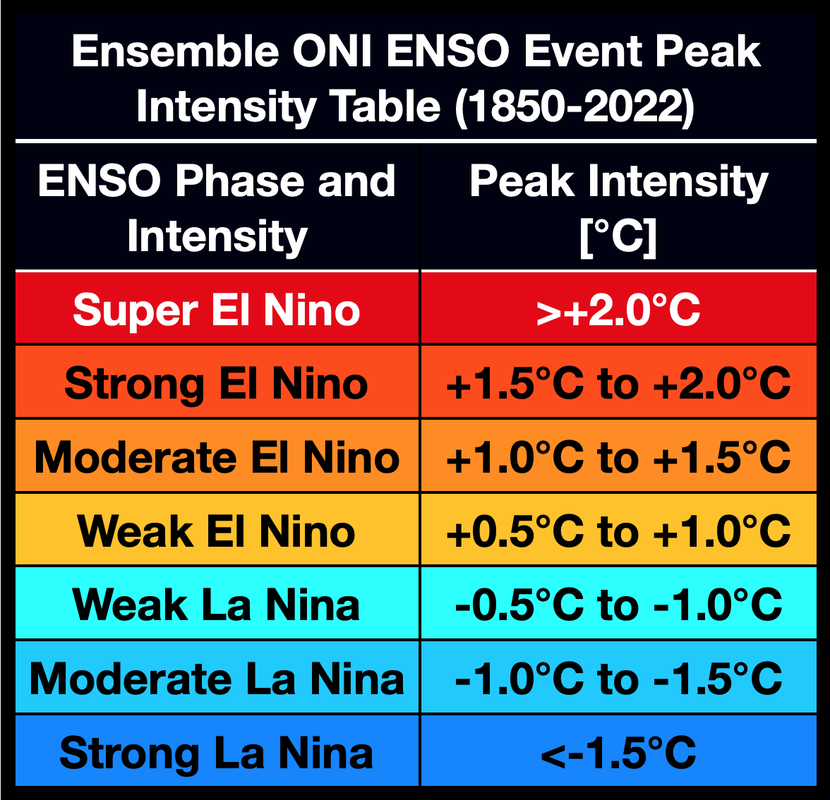

ENSO phase and intensity

Thus, going by the definition of ENSO noted here, El Ninos occur when the ENS ONI values are in the top 33% of all ENS ONI values for each tri-monthly period, while Neutral ENSO and La Nina correspond to the middle third and lower third of bi-monthlies respectively. Further distinctions to denote Weak, Moderate, Strong, and Super (very strong) ENSO events were also made here as was done with MEI.ext and MEI. Similar to Wolter and Timlin (2011), moderate El Ninos and moderate La Ninas were assumed to be ongoing when the MEI.extv2 bi-monthly percentiles were in the 2nd (10-20%) and 9th deciles (80-90%) respectively. Also similar to Wolter and Timlin (2011), the minimum threshold for Strong El Nino and Strong La Nina is defined as the 10th and 90th percentiles respectively.

A further distinction is made to identify extraordinarily powerful El Nino and La Nina events. The motivation for this is attributable to the fact that 4 very intense El Nino events (1877-78, 1982-83, 1997-98, 2015-16) are all more intense than not only any other El Nino, but all other ENSO events in the observed record. Furthermore, all of these El Ninos events have triggered exceptionally large and widespread climate anomalies across the globe, and the term “Super El Nino” has become increasingly popular and acceptable nomenclature in the atmospheric science community (Hameed et al (2018); Zhu et al (2018); Bing and Xie (2017); Chen et al (2016); Hong (2016); Latif et al (2015).

Created using Matlab 2022b

ENSO Definitions

This unique analysis of many ENSO definitions also allows us to obtain an estimate of opinions from experts in the field on what is and is not ENSO at some time "t" based on output from the ENS ONI; a crude measure of consensus.

Considering all of the above, it seems reasonable to believe that when at least a majority of the 50 definitions (25 of 50 (or more)) reach a consensus that an El Nino or La Nina is ongoing for a given monthly, bi-monthly, tri-monthly, and/or pentad period based on the ENS ONI, that an ENSO event is indeed probably, if not, likely ongoing. We will tentatively refer to this measure of ENSO as the ENS ONI Definitions Index. In order to ensure an apples-apples comparison between all the definitions, each one is given equivalent weight of up to 1 w/ a binary output (1 or 0/pass or fail) signaling the specified criteria in each definition was or was not met at a particular time step. To determine the time that this actually corresponds to for instances where tri-monthly or pentad averaged values of this ENS ONI are used, the middle month of that period is utilized. For ex, if we're looking at an ENSO definition that uses a pentad-averaged period to categorize ENSO and we're analyzing Oct-Feb (ONDJF), the binary output would be placed in the month of December, w/ January being used in place of NDJFM, etc. For bi-monthlies, these ENS ONI Definitions index values are binned into the first month of the bi-monthly period. To designate both El Ninos and La Ninas in this paradigm, La Nina (El Nino) values are negative (positive) and shaded blue (red).

Depicted in Table 6 is the ENS ONI Median Definitions Index for 2010-present. Raw values (0 to (+ or -) 50) are converted to percent, with values <-49(%) signifying that a majority of ENSO definitions recognize La Nina conditions, whereas values >+49 (%) correspond to where most definitions contend that El Nino conditions are occurring. Note that this definitions index will lag in real-time by a few months, due to the inclusion of literature-based ENSO definitions that are dependent on pentad (5-month) averaged data.

Hyperlinked Excel file for the ENS ONI definitions index (evaluated on the median SST anomaly value presented here)

ENS ONI Median Definition Index (1850 - Feb 2024)

**Assessments and further applications of this ENS ONI Definitions Index (esp as it pertains to uncertainty) are currently being experimented with and may be released in the future**

Institution/Reference(s) |

Criteria Amplitude |

Criteria Length |

> +/- 0.75°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.7σ SST |

3 tri-monthlies |

|

> +/- 0.8°C SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

6 consecutive pentads |

|

> +/- 0.75σ SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 1.0°C SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 2.0°C SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

6 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 1.0°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

El Nino: 25th %ile, La Nina: 75th %ile |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

Any month |

|

El Nino: 25th %ile, La Nina: 75th %ile |

Any month |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

4 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.7σ SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

6 consecutive pentads |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

3 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

6 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 1.2σ SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

2 consecutive tri-monthlies |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.6°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

5 consecutive tri-monthlies |

|

> +/- 0.7σ SST |

4 month period |

|

> +/- 1.4°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 1.0°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

5 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.75σ SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

El Nino: 33rd %ile, La Nina: 67th %ile |

1 pentad |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

1 pentad |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

5 consecutive pentads |

|

> +/- 0.4°C SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

Any month |

|

> +/- 0.4σ SST |

4 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 1.0°C SST |

3 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.4°C SST |

3 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.4°C SST |

6 consecutive tri-monthlies |

|

> +/- 1.0σ SST |

1 pentad |

|

> +/- 0.25°C SST |

5 consecutive tri-monthlies |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

8 months |

|

> +/- 1.5°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.6°C SST |

1 pentad |

|

El Nino: 30th %ile, La Nina: 70th %ile |

1 bi-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.5σ SST |

5 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

> +/- 0.4°C SST |

1 pentad |

|

> +/- 0.5°C SST |

1 pentad |

|

> +/- 1.0°C SST |

5 consecutive months |

|

> +/- 0.6σ SST |

1 tri-monthly |

|

ENS ONI Literature-Based Definitions Index (%

ENSO Definitions Met) |

||||||||||||

|

JAN |

FEB |

MAR |

APR |

MAY |

JUN |

JUL |

AUG |

SEP |

OCT |

NOV |

DEC |

|

|

2010 |

94% |

92% |

88% |

28% |

-4% |

-82% |

-94% |

-94% |

-98% |

-98% |

-98% |

-98% |

|

2011 |

-96% |

-94% |

-88% |

-86% |

-76% |

-40% |

-34% |

-62% |

-70% |

-82% |

-84% |

-84% |

|

2012 |

-70% |

-66% |

-60% |

-36% |

-12% |

0% |

2% |

22% |

16% |

2% |

0% |

0% |

|

2013 |

-4% |

-6% |

-2% |

-4% |

-16% |

-28% |

-18% |

-10% |

-2% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

2014 |

-2% |

-8% |

-2% |

0% |

0% |

4% |

0% |

0% |

2% |

20% |

44% |

42% |

|

2015 |

42% |

38% |

50% |

80% |

86% |

88% |

94% |

98% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

2016 |

100% |

100% |

98% |

86% |

18% |

0% |

-20% |

-42% |

-40% |

-46% |

-42% |

-32% |

|

2017 |

-6% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

2% |

4% |

2% |

0% |

-14% |

-48% |

-68% |

-68% |

|

2018 |

-68% |

-68% |

-68% |

-54% |

-16% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

12% |

54% |

66% |

68% |

|

2019 |

58% |

60% |

72% |

66% |

60% |

40% |

20% |

0% |

0% |

6% |

10% |

10% |

|

YR |

JAN |

FEB |

MAR |

APR |

MAY |

JUN |

JUL |

AUG |

SEP |

OCT |

NOV |

DEC |

|

2020 |

12% |

4% |

10% |

8% |

-4% |

-22% |

-32% |

-62% |

-82% |

-92% |

-92% |

-88% |

|

2021 |

-88% |

-82% |

-70% |

-62% |

-40% |

-18% |

-18% |

-32% |

-50% |

-80% |

-78% |

-80% |

|

2022 |

-74% |

-82% |

-92% |

-92% |

-92% |

-86% |

-84% |

-88% |

-88% |

-90% |

-86% |

-70% |

|

2023 |

-68% |

-34% |

-2% |

0% |

22% |

80% |

86% |

94% |

96% |

98% |

98% |

98% |

|

2024 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Raw Monthly NINO 3.4 SST Input (1850 - Feb 2024)

Monthly NINO 3.4 SSTs (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI Median Definitions Index (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI Monthly Data (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI tri-monthly (CPC-like) data (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI standardized tri-monthly data (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI tri-monthly ranks (1850 - Feb 2024)

ENS ONI, NOAA 20CRv3, & HADISST2.1 uncertainty (1850 - Feb 2024)

The following ENS ONI table (also linked above) uses a modified version of Webb and Magi (2021)'s definition of ENSO. Here, 50 literature-based definitions (table 5) are used instead of 33, and if at least 50% of these ENSO definitions are met surrounding a particular month, it is recognized as a legitimate El Nino (red) or La Nina (blue), irrespective of the event's duration and/or potential discontinuities wrt adjacent months.

|

Ensemble Oceanic Nino

Index (ENS ONI) |

||||||||||||

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1850 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.2 |

-0.6 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

1851 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

|

1852 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

1853 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

1854 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

1855 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

1856 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

|

1857 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1858 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1859 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1860 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

1861 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1862 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

|

1863 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1864 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

1865 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

|

1866 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

1867 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

|

1868 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

1869 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1870 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

|

1871 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1872 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

|

1873 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

|

1874 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

|

1875 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

1876 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

|

1877 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

|

1878 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

|

1879 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

|

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

|

1880 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

|

1881 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1882 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

1883 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

1884 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

1885 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

1886 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

|

1887 |

-1.2 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

1888 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

1889 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.4 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1890 |

-1.4 |

-1.3 |

-1.1 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

|

1891 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

|

1892 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.2 |

-1.4 |

-1.4 |

-1.2 |

|

1893 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

|

1894 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

|

1895 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

|

1896 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

1897 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

1898 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

|

1899 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

|

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

|

1900 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

1901 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1902 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

1903 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

|

1904 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

1905 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

1906 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

|

1907 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1908 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

|

1909 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1910 |

-1.1 |

-1.2 |

-1.2 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

|

1911 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

|

1912 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

1913 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

1914 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

1915 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

|

1916 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.4 |

-1.7 |

-2.1 |

-2.1 |

|

1917 |

-1.9 |

-1.7 |

-1.3 |

-1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

|

1918 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

|

1919 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1920 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

1921 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

1922 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

|

1923 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

1924 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

|

1925 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

|

1926 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

1927 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

1928 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1929 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1930 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

|

1931 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

|

1932 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1933 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

|

1934 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

1935 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

1936 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

1937 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

1938 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

|

1939 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1940 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

|

1941 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

1942 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.6 |

-0.9 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.2 |

-1.2 |

|

1943 |

-1.2 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

1944 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

1945 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

1946 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

|

1947 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

|

1948 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

1949 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

|

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

|

1950 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

|

1951 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

1952 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

1953 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

1954 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

|

1955 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-1.1 |

-1.4 |

-1.5 |

-1.4 |

|

1956 |

-1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

|

1957 |

-0.3 |

-0.0 |

-0.3 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

|

1958 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

|

1959 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1960 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1961 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

|

1962 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

1963 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

1964 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

|

1965 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

|

1966 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

|

1967 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

|

1968 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

1969 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1970 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

|

1971 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

|

1972 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

|

1973 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.3 |

-1.5 |

-1.7 |

|

1974 |

-1.6 |

-1.4 |

-1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

|

1975 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.2 |

-1.3 |

-1.4 |

|

1976 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

1977 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

1978 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

1979 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1980 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

|

1981 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

1982 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

|

1983 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

|

1984 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.8 |

-1.1 |

|

1985 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

|

1986 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

1987 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

|

1988 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

-0.5 |

-1.0 |

-1.4 |

-1.5 |

-1.4 |

-1.5 |

-1.7 |

-2.1 |

-2.1 |

|

1989 |

-1.9 |

-1.6 |

-1.3 |

-1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

1990 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

1991 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

|

1992 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1993 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

1994 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

1995 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

|

1996 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

|

1997 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

|

1998 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

0.3 |

-0.4 |

-1.1 |

-1.2 |

-1.2 |

-1.2 |

-1.4 |

-1.4 |

|

1999 |

-1.3 |

-1.1 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.3 |

-1.5 |

|

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

|

2000 |

-1.5 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

|

2001 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

2002 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

|

2003 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

2004 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

2005 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.7 |

|

2006 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

2007 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

-1.1 |

-1.4 |

-1.6 |

-1.6 |

|

2008 |

-1.7 |

-1.6 |

-1.4 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

|

2009 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

2010 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.7 |

-1.1 |

-1.3 |

-1.5 |

-1.6 |

-1.7 |

-1.6 |

|

2011 |

-1.5 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

|

2012 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

2013 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

|

2014 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

|

2015 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

|

2016 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

|

2017 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

-0.9 |

|

2018 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

2019 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

YR |

DJF |

JFM |

FMA |

MAM |

AMJ |

MJJ |

JJA |

JAS |

ASO |

SON |

OND |

NDJ |

|

2020 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-1.0 |

-1.2 |

-1.3 |

-1.2 |

|

2021 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

|

2022 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-0.9 |

|

2023 |

-0.8 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

|

2024 |

1.7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

References

Allan, R. J., et al. (2002). "A reconstruction of Madras (Chennai) mean sea-level pressure using instrumental records from the late 18th and early 19th centuries." International Journal of Climatology 22(9): 1119-1142.

Allan, R.J., Nicholls, N., Jones, P.D. and Butterworth, I.J. (1991) A further extension of the Tahiti-Darwin SOI, early ENSO events and Darwin pressure. Journal of Climate, 4, 743– 749.

Amaya, D. J. and G. R. Foltz (2014). "Impacts of canonical and Modoki El Niño on tropical Atlantic SST." Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 119(2): 777-789.

An, S.-I. and F.-F. Jin (2004). "Nonlinearity and asymmetry of ENSO." Journal of Climate 17(12): 2399-2412.

An, S.-I. and Kim, J.-W. (2017) Role of nonlinear ocean dynamic response to wind on the asymmetrical transition of El Niño and La Niña. Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 393– 400.

An, S.-I. and Kim, J.-W. (2018) ENSO transition asymmetry: internal and external causes and intermodel diversity. Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 5095– 5104.

Anderson, D.M., Mauk, E.M., Wahl, E.R., Morrill, C., Wagner, A.J., Easterling, D. and Rutishauser, T.(2013) Global warming in an independent record of the past 130 years. Geophysical Research Letters, 40, 189– 193.

Ashok, K., Behera, S.K., Rao, S.A., Weng, H. and Yamagata, T. (2007) El Niño Modoki and its possible teleconnection. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 112, C11007.

Ault, T.R., Deser, C., Newman, M. and Emile-Geay, J. (2013) Characterizing decadal to centennial variability in the equatorial Pacific during the last millennium. Geophysical Research Letters, 40, 3450– 3456.

Australian Bureau of Meteorology. “About ENSO and IOD indices”. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/indices/about.shtml

Barnston, A.G., Chelliah, M. and Goldenberg, S.B. (1997) Documentation of a highly ENSO-related sst region in the equatorial Pacific: research note. Atmosphere-Ocean, 35, 367– 383.

Bing, Z. and S. Xie (2017). "The 2015/16 “Super” El Niño Event and Its Climatic Impact." Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies 05(03): 1750017.

Bjerknes, J. (1966) A possible response of the atmospheric Hadley circulation to equatorial anomalies of ocean temperature. Tellus, 18, 820– 829.

Bjerknes, J. (1969) Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Monthly Weather Review, 97, 163– 172.

Bove, M.C., Elsner, J.B., Landsea, C.W., Niu, X. and O'Brien, J.J. (1998) Effect of El Niño on US landfalling hurricanes, revisited. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 79, 2477– 2482.

Braganza, K., Gergis, J.L., Power, S.B., Risbey, J.S. and Fowler, A.M. (2009) A multiproxy index of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, A.D. 1525–1982. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 114, D05106.

Butler, A. H. and L. M. Polvani (2011). "El Niño, La Niña, and stratospheric sudden warmings: A reevaluation in light of the observational record." Geophysical Research Letters 38(13).

Cai, W., McPhaden, M.J., Grimm, A.M. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on South America. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1, 215–231 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0040-3

Callahan, C. W., et al. (2021). "Robust decrease in El Niño/Southern Oscillation amplitude under long-term warming." Nature Climate Change 11(9): 752-757.

Carella, G., Kennedy, J.J., Berry, D.I., Hirahara, S., Merchant, C.J., Morak-Bozzo, S. and Kent, E.C.(2018) Estimating sea surface temperature measurement methods using characteristic differences in the diurnal cycle. Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 363– 371.

Chen, D., Cane, M.A., Kaplan, A., Zebiak, S.E. and Huang, D. (2004) Predictability of El Niño over the past 148 years. Nature, 428, 733– 736.

Chen, L., et al. (2016). "Distinctive precursory air–sea signals between regular and super El Niños." Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 33(8): 996-1004.

Choi, K.-Y., Vecchi, G.A. and Wittenberg, A.T. (2013) ENSO transition, duration, and amplitude asymmetries: role of the nonlinear wind stress coupling in a conceptual model. Journal of Climate, 26, 9462– 9476.

Climate Prediction Center. (2005). El Nino Regions. Retrieved from: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ninoareas_c.jpg

Coelho, C.A.S., Uvo, C.B. and Ambrizzi, T. (2002) Exploring the impacts of the tropical Pacific SST on the precipitation patterns over South America during ENSO periods. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 71, 185– 197.

Compo, G. P., et al. (2011). "The Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project." Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 137(654): 1-28.

Cook, E., D'Arrigo, R. & Anchukaitis, K. (2008) ENSO reconstructions from long tree-ring chronologies: Unifying the differences. Talk presented at a special workshop on Reconciling ENSO Chronologies for the Past, 2008.

Cram, T.A., et al. (2015) The International Surface Pressure Databank version 2. Geoscience Data Journal, 2, 31– 46.

Dai, A. and Wigley, T.M.L. (2000) Global patterns of ENSO-induced precipitation. Geophysical Research Letters, 27, 1283– 1286.

Dätwyler, C., Grosjean, M., Steiger, N.J. and Neukom, R. (2020) Teleconnections and relationship between the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the southern annular mode (SAM) in reconstructions and models over the past millennium. Climate of the Past, 16, 743– 756.

Dee, D. P., et al. (2011). "The ERA‐Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system." Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 137(656): 553-597.

Deser, C. and Wallace, J.M. (1987) El Niño events and their relation to the Southern Oscillation: 1925–1986. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 92, 14189– 14196.

DiNezio, P. N. and C. Deser (2014). "Nonlinear Controls on the Persistence of La Niña*." Journal of Climate 27(19): 7335-7355.

Douglas Schuster, N. (2010). Content, discovery, and accessibility enhancements to the NCAR Research Data Archive. 26th Conference on Interactive Information and Processing Systems.

Enfield, D.B. (1989) El Niño, past and present. Reviews of Geophysics, 27, 159– 187.

Enfield, D.B. and Cid, S.L. (1991) Low-frequency changes in El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Journal of Climate, 4, 1137– 1146.

Folland, C.K., Parker, D.E. and Kates, F.E. (1984) Worldwide marine temperature fluctuations 1856–1981. Nature, 310, 670– 673.

Folland, C. K. and D. E. Parker (1995). "Correction of instrumental biases in historical sea surface temperature data." Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 121(522): 319-367.

Fredriksen, H.-B., Berner, J., Subramanian, A.C. and Capotondi, A. (2020) How does El Niño–Southern Oscillation change under global warming—a first look at CMIP6. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2020GL090640.

Freeman, E., et al. (2017). "ICOADS Release 3.0: a major update to the historical marine climate record." International Journal of Climatology 37(5): 2211-2232.

Freund, M.B., Henley, B.J., Karoly, D.J., McGregor, H.V., Abram, N.J. and Dommenget, D. (2019) Higher frequency of central Pacific El Niño events in recent decades relative to past centuries. Nature Geoscience, 12, 450– 455.

Garcia-Herrera, R., et al. (2008). "A Chronology of El Niño Events from Primary Documentary Sources in Northern Peru*." Journal of Climate 21(9): 1948-1962.

Garfinkel, C. I., et al. (2019). "The salience of nonlinearities in the boreal winter response to ENSO: North Pacific and North America." Climate Dynamics 52(7): 4429-4446.

Gelaro, R., et al. (2017). "The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2)." Journal of Climate 30(14): 5419-5454.

Gergis, J.L. and Fowler, A.M. (2005) Classification of synchronous oceanic and atmospheric El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events for palaeoclimate reconstruction. International Journal of Climatology, 25, 1541– 1565.

Gergis, J.L. and Fowler, A.M. (2009) A history of ENSO events since A.D. 1525: implications for future climate change. Climatic Change, 92, 343– 387.

Giese, B.S., Compo, G.P., Slowey, N.C., Sardeshmukh, P.D., Carton, J.A., Ray, S. and Whitaker, J.S.(2010) The 1918/19 El Niño. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 91, 177– 183.

Giese, B.S. and Ray, S. (2011) El Niño variability in simple ocean data assimilation (SODA), 1871–2008. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116, C02024.

Giese, B.S., Seidel, H.F., Compo, G.P. and Sardeshmukh, P.D. (2016) An ensemble of ocean reanalyses for 1815–2013 with sparse observational input. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121, 6891– 6910.

Glantz, M. H. and I. J. Ramirez (2020). "Reviewing the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) to enhance societal readiness for El Niño’s impacts." International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11(3): 394-403.

Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) Working Group on Surface Pressure (WG-SP). (2018). www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/gcos_wgsp/

Goddard, L. and M. Dilley (2005). "El Niño: catastrophe or opportunity." Journal of Climate 18(5): 651-665.

Guilyardi, E. (2006). "El Niño–mean state–seasonal cycle interactions in a multi-model ensemble." Climate Dynamics 26(4): 329-348.

Hakim, G.J., Emile-Geay, J., Steig, E.J., Noone, D., Anderson, D.M., Tardif, R., Steiger, N. and Perkins, W.A. (2016) The last millennium climate reanalysis project: framework and first results. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 121, 6745– 6764.

Ham, Y.-G. and J.-S. Kug (2012). "How well do current climate models simulate two types of El Niño?" Climate Dynamics 39(1): 383-398.

Hameed, S. N., et al. (2018). "A model for super El Niños." Nature Communications 9(1): 2528.

Hanley, D.E., Bourassa, M.A., O'Brien, J.J., Smith, S.R. and Spade, E.R. (2003) A quantitative evaluation of ENSO indices. Journal of Climate, 16, 1249– 1258.

Hausfather, Z., Cowtan, K., Clarke, D.C., Jacobs, P., Richardson, M. and Rohde, R. (2017) Assessing recent warming using instrumentally homogeneous sea surface temperature records. Science Advances, 3, e1601207.

Hayashi, M. and F. F. Jin (2017). "Subsurface nonlinear dynamical heating and ENSO asymmetry." Geophysical Research Letters 44(24): 12,427-412,435.

Hendon, H.H., Lim, E., Wang, G., Alves, O. and Hudson, D. (2009) Prospects for predicting two flavors of El Niño. Geophysical Research Letters, 36, L19713.

Hennermann, K. and Berrisford, P.: What are the changes from ERA-Interim to ERA5? (2018). https://confluence.ecmwf.int/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=74764925

Hersbach, H., et al. (2020) The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146, 1999– 2049.

Hersbach, H., et al. (2015). "ERA-20CM: a twentieth-century atmospheric model ensemble." Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 141(691): 2350-2375.

Hirahara, S., et al. (2014). "Centennial-Scale Sea Surface Temperature Analysis and Its Uncertainty." Journal of Climate 27(1): 57-75.

Hong, L.-C. (2016). Super El Niño, Springer.

Hu, Z.-Z., et al. (2014). "Why were some La Niñas followed by another La Niña?" Climate Dynamics 42(3): 1029-1042.

Huang, B., et al. (2015). "Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature Version 4 (ERSST.v4). Part I: Upgrades and Intercomparisons." Journal of Climate 28(3): 911-930.

Huang, B., et al. (2016). "Further Exploring and Quantifying Uncertainties for Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST) Version 4 (v4)." Journal of Climate 29(9): 3119-3142.

Huang, B., et al. (2016). "Ranking the strongest ENSO events while incorporating SST uncertainty." Geophysical Research Letters 43(17): 9165-9172.

Huang, B., et al. (2017). "Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons." Journal of Climate 30(20): 8179-8205.

Huang, B., et al. (2020). "How Significant Was the 1877/78 El Niño?" Journal of Climate 33(11): 4853-4869.

Hurwitz, M., et al. (2011). "Response of the Antarctic stratosphere to two types of El Niño events." Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 68(4): 812-822.

Ishii, M., et al. (2005). "Objective analyses of sea-surface temperature and marine meteorological variables for the 20th century using ICOADS and the Kobe Collection." International Journal of Climatology 25(7): 865-879.

Japan Meteorological Agency. "El Nino Monitoring and Outlook" ds.data.jma.go.jp/tcc/tcc/products/elnino/elmonout.html

Jiang, W., Huang, P., Huang, G. and Ying, J. (2021) Origins of the excessive westward extension of ENSO SST simulated in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Journal of Climate, 34, 2839– 2851.

Kalnay, E., et al. (1996) The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 77, 437– 472.

Kanamitsu, M., et al. (2002). "Ncep–doe amip-ii reanalysis (r-2)." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 83(11): 1631-1644.

Kao, H.-Y. and Yu, J.-Y. (2009) Contrasting eastern-Pacific and central-Pacific types of ENSO. Journal of Climate, 22, 615– 632.

Kaplan, A., et al. (1998). "Analyses of global sea surface temperature 1856–1991." Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 103(C9): 18567-18589.

Karl, T.R., Arguez, A., Huang, B., Lawrimore, J.H., McMahon, J.R., Menne, M.J., Peterson, T.C., Vose, R.S. and Zhang, H.-M. (2015) Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus. Science, 348, 1469– 1472.

Karnauskas, K. B., et al. (2012). "A Pacific Centennial Oscillation Predicted by Coupled GCMs*." Journal of Climate 25(17): 5943-5961.

Keeley, S. (2018). “ECMWF Climate Reanalysis” www.ecmwf.int/en/research/climate-reanalysis.

Kennedy, J. J., et al. (2011). "Reassessing biases and other uncertainties in sea surface temperature observations measured in situ since 1850: 1. Measurement and sampling uncertainties." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 116(D14).

Kennedy, J. J. (2014). "A review of uncertainty in in situ measurements and data sets of sea surface temperature." Reviews of Geophysics 52(1): 1-32.

Kennedy, J. J., et al. (2019). "An ensemble data set of sea-surface temperature change from 1850: the Met Office Hadley Centre HadSST.4.0.0.0 data set." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 0(ja).

Kent, E. C., et al. (2013). "Global analysis of night marine air temperature and its uncertainty since 1880: The HadNMAT2 data set." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 118(3): 1281-1298.

Kent, E.C., et al. (2017) A call for new approaches to quantifying biases in observations of sea surface temperature. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 98, 1601– 1616.

Kessler, W. S. (2002). "Is ENSO a cycle or a series of events?" Geophysical Research Letters 29(23): 40-41-40-44.

Khodri, M., et al. (2017). "Tropical explosive volcanic eruptions can trigger El Niño by cooling tropical Africa." Nature Communications 8(1): 1-13.

Kiladis, G. N. and H. F. Diaz (1986). "An Analysis of the 1877–78 ENSO Episode and Comparison with 1982–83." Monthly Weather Review 114(6): 1035-1047.

Ku, H. H. (1966). "Notes on the use of propagation of error formulas." Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 70(4): 263-273.

Kug, J.-S., et al. (2009). "Two types of El Niño events: cold tongue El Niño and warm pool El Niño." Journal of Climate 22(6): 1499-1515.

L'Heureux, M.L., et al. (2017) Observing and predicting the 2015/16 El Niño. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 98, 1363– 1382.

Laloyaux, P., et al. (2018). "CERA-20C: A Coupled Reanalysis of the Twentieth Century." Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 10(5): 1172-1195.

Langton, S.J., et al. (2008) 3500 yr record of centennial-scale climate variability from the Western Pacific Warm Pool. Geology, 36, 795– 798.

Latif, M., et al. (2015). "Super El Niños in response to global warming in a climate model." Climatic Change 132(4): 489-500.

Lemmon, D. E. and K. B. Karnauskas (2019). "A metric for quantifying El Niño pattern diversity with implications for ENSO–mean state interaction." Climate Dynamics 52(12): 7511-7523.

Levine, A.F.Z. and McPhaden, M.J. (2016) How the July 2014 easterly wind burst gave the 2015–2016 El Niño a head start. Geophysical Research Letters, 43, 6503– 6510.

Lewis, S.C. and LeGrande, A.N. (2015) Stability of ENSO and its tropical Pacific teleconnections over the Last Millennium. Climate of the Past, 11, 1347– 1360.

Li, J., et al. (2011) Interdecadal modulation of El Niño amplitude during the past millennium. Nature Climate Change, 1, 114– 118.

Lin, K. H. E., et al. (2020). "Historical droughts in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) of China." Clim. Past 16(3): 911-931.

Liu, W., et al. (2015). "Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature Version 4 (ERSST.v4): Part II. Parametric and Structural Uncertainty Estimations." Journal of Climate 28(3): 931-951.

Liu, Y., et al. (2017) Recent enhancement of central Pacific El Niño variability relative to last eight centuries. Nature Communications, 8, 15386.

Luan, Y., et al. (2012) Early and mid-Holocene climate in the tropical Pacific: seasonal cycle and interannual variability induced by insolation changes. Climate of the Past, 8, 1093– 1108.

Lucena, D.B., et al. (2011) Rainfall response in Northeast Brazil from ocean climate variability during the second half of the twentieth century. Journal of Climate, 24, 6174– 6184.

McGregor, S., et al. (2013) Inferred changes in El Niño–Southern Oscillation variance over the past six centuries. Climate of the Past, 9, 2269– 2284.

McGregor, S., et al. (2010) A unified proxy for ENSO and PDO variability since 1650. Climate of the Past, 6, 1– 17.

McPhaden, M.J. (1999) Genesis and evolution of the 1997–98 El Niño. Science, 283, 950– 954.

McPhaden, M.J., et al. (2020) El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

McPhaden, M.J., et al. (2015) The curious case of the EL Niño that never happened: a perspective from 40 years of progress in climate research and forecasting. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 96, 1647– 1665.

Meehl, G.A., et al. (2006) Future changes of El Niño in two global coupled climate models. Climate Dynamics, 26, 549– 566.

Morice, C.P., et al. (2021) An updated assessment of near-surface temperature change from 1850: the HadCRUT5 data set. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 126, e2019JD032361.

NASA. (2018). “NASA Earth Observations” neo.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/view.php?datasetId=MYD28M.

Neelin, J.D., et al (1998) ENSO theory. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 103, 14261– 14290.

Nguyen, P. L., et al. (2021). "Combined impacts of the El Niño‐Southern Oscillation and Pacific decadal oscillation on global droughts assessed using the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index." International Journal of Climatology 41: E1645-E1662.

Null, J. (2018) “El Nino and La Nina Years and Intensities”. ggweather.com/enso/oni.htm

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. “Cold and Warm Episodes by Season”. origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php

NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory. (2020). https://esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/

NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. (2018). “Equatorial Pacific Sea Surface Temperatures” www.ncdc.noaa.gov/teleconnections/enso/indicators/sst/

O'Carroll, A.G., et al. (2019) Observational needs of sea surface temperature. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 420.

Ohba, M. and Ueda, H. (2009) Role of nonlinear atmospheric response to SST on the asymmetric transition process of ENSO. Journal of Climate, 22, 177– 192.

Ohba, M. and Watanabe, M. (2012) Role of the Indo-Pacific Interbasin coupling in predicting asymmetric ENSO transition and duration. Journal of Climate, 25, 3321– 3335.

Okumura, Y.M. and Deser, C. (2010) Asymmetry in the duration of El Niño and La Niña. Journal of Climate, 23, 5826– 5843.

Okumura, Y. M., et al. (2011). "A proposed mechanism for the asymmetric duration of El Niño and La Niña." Journal of Climate 24(15): 3822-3829.

Ortlieb, L. (2000). The Documented Historical Record of El Nino Events in Peru: An Update of the Quinn Record (Sixteenth through Nineteenth Centuries): 207-295.

Parker, W. S. (2016). "Reanalyses and Observations: What’s the Difference?" Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 97(9): 1565-1572.